Last night, my mind was racing. My thoughts were whirring by so fast I could hardly catch them. My heart rate soared and my chest pounded and sleep got farther away. The theme? Enough. Am I working hard enough at my job? Am I talented enough to make music? Am I beautiful enough to find love? After what seemed like hours of this I said “enough is enough,” took a melatonin, and forced myself asleep. But that didn’t make them go away, of course. They always find a way to creep back.

Today, my mind was racing. The theme? Chametz. For a number of reasons:

We kashered our apartment today! Oven? clean. Fridge? clean. I draped colorful sheets over the remaining food and appliances, and blue-taped the cabinets shut. So that’s it. No more chametz up in here.

My music classes have been learning ma nishtana, the four questions, since January. Each week, we would go over the questions and talk about what they mean. Today I asked them: What does Chametz mean? At least one student in each class raised their hand and answered, with confidence, “matzah!” Sigh.

I made a video for a ridiculous song I wrote about Bedikat Chametz. Which leads to the fourth chametz:

Ego. I really like this song. I really want people to hear it. I’m really uncomfortable saying that out loud. I keep checking for the YouTube views to go up, but how are people supposed to watch it if I don’t post about it?

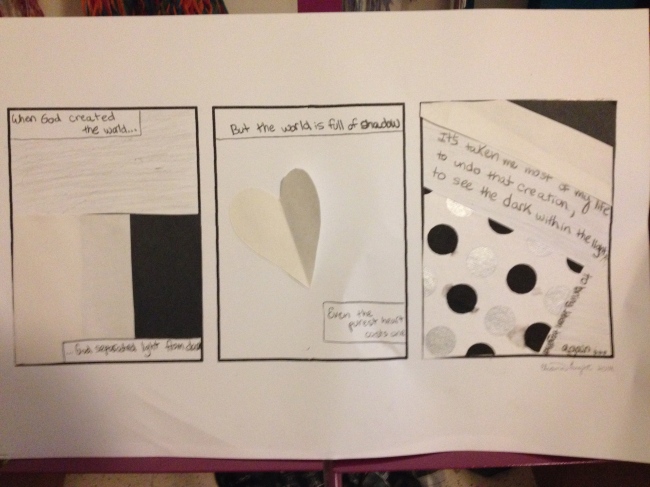

One of the interpretations of chametz is that it represents ego, our puffed-up ideas of ourselves. Passover comes along and tells us to get rid of it. We must flatten ourselves, just like the matzah we will eat for the next eight days (or seven, if you’re Reform, or live in Israel.) This is such a beautiful sentiment, using ritual to connect our outsides to our insides. But for someone like me, this is tough, because of, well, “enough.” I already have anxiety around ego, but usually in the opposite direction. I believe in my work, but I don’t want to be self-involved, and self-serving. And I don’t want to come across that way. What is the balance?

I got a little closer to finding it today. In a deep breath. Here’s how I got there.

A few days ago I spent the morning with a wonderful friend, a certain pink-haired song-leader lady from Australia. (those who know, know! 🙂 She could tell from my stories that I was a bit down: down on myself, down on work, down on New York. She could sense the “enoughs” creeping through. So she asked me, “Do you have a place in New York that is your favorite? That you go to when you need to feel better?” The first place that came to mind is a little spot in central park, right by the entrance by my street. You climb in over some rocks, and can sit right next to a mini-waterfall, hear the water rush down, see the brook, smell the trees… it is a nice oasis of nature in this crazy city. And my friend’s plan worked: I smiled just thinking about it. So on my way home from work today I decided to stop there. I settled in on a rock, and decided to try something some other friends keep suggesting: meditating. I’m not so good at it, but I figured it couldn’t hurt. So I closed my eyes, and took a deep breath….

And then I let it out. And I did it again. Deep breath in….

And out. And I thought, “I am puffing myself up.” Deep breath in….

And out. “I am like chametz.” Deep breath in…

And out. “But unlike bread, I can’t stay puffed up.” Deep breath in…

And out. “I would burst. I need to exhale.” Deep breath in….

And out. “Maybe I’m allowed to be puffed up,” Deep breath in…

And out. “If I don’t keep it in, but share it with everyone.

The 3 minute timer on my phone went off.

I can let myself puff up. I can fill my lungs with air. I can feel good about my work. I can be proud of what I do. And then, I exhale. I share my gifts. I realize that the work I do is to help others learn, grow, sing, and shine. I add my spirit, my air, to the all-enveloping Ruach that gives us life.

Flour and water make chametz, but they also make matzah. I can have ego and humility. I can love what I do and know that I do it for us, not me. And that can be enough. Dayeinu.

And because I do think this song teaches an obscure Jewish ritual in a fun, engaging way, I will share it with you:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7hO1JnObgbQ&feature=youtu.be